Pre-1948

Introduction

The roots of the Hatton Gallery and the Newcastle University Fine Art Department, both housed in the King Edward VII building opened in 1912, go back to the 1830s and the formation of the ‘North of England Society for the promotion of the Fine Arts in their Higher Departments, and in their Application to Manufactures’. In 1838 a School of Art associated with this Society was established, which by 1844 had made connections with the new Government School of Design in Somerset House, London (itself the root of the current Royal College of Art), who appointed the artist William Bell Scott to be Master in Newcastle, a position he held for 20 years.

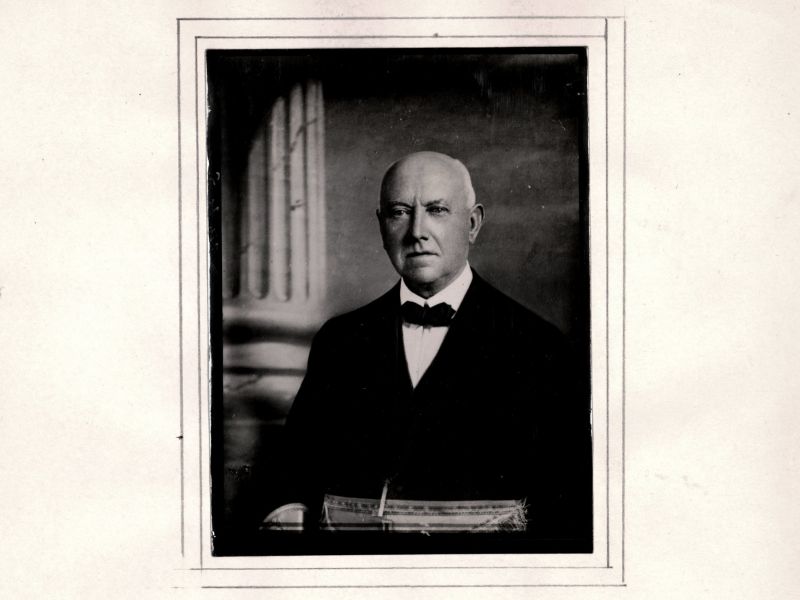

In 1888, then led by William Cosens Way, the School found new accommodation within Durham University’s College of Physical Science (later renamed Armstrong College), founded in 1871. Shortly after in 1890 it was recommended by Cosens Way that Mr R.G. Hatton of the Municipal School of Art, Birmingham be appointed as Second Master. This was part of an increasing professionalisation of the School and establishment of closer ties to the University.

In 1894 a new prospectus was published now describing the School as the ‘Department of Fine Art’, the Principal was still Cosens Way, though he would be replaced by Hatton the following year, Geometry and Perspective was taught by Ralph Bullock.

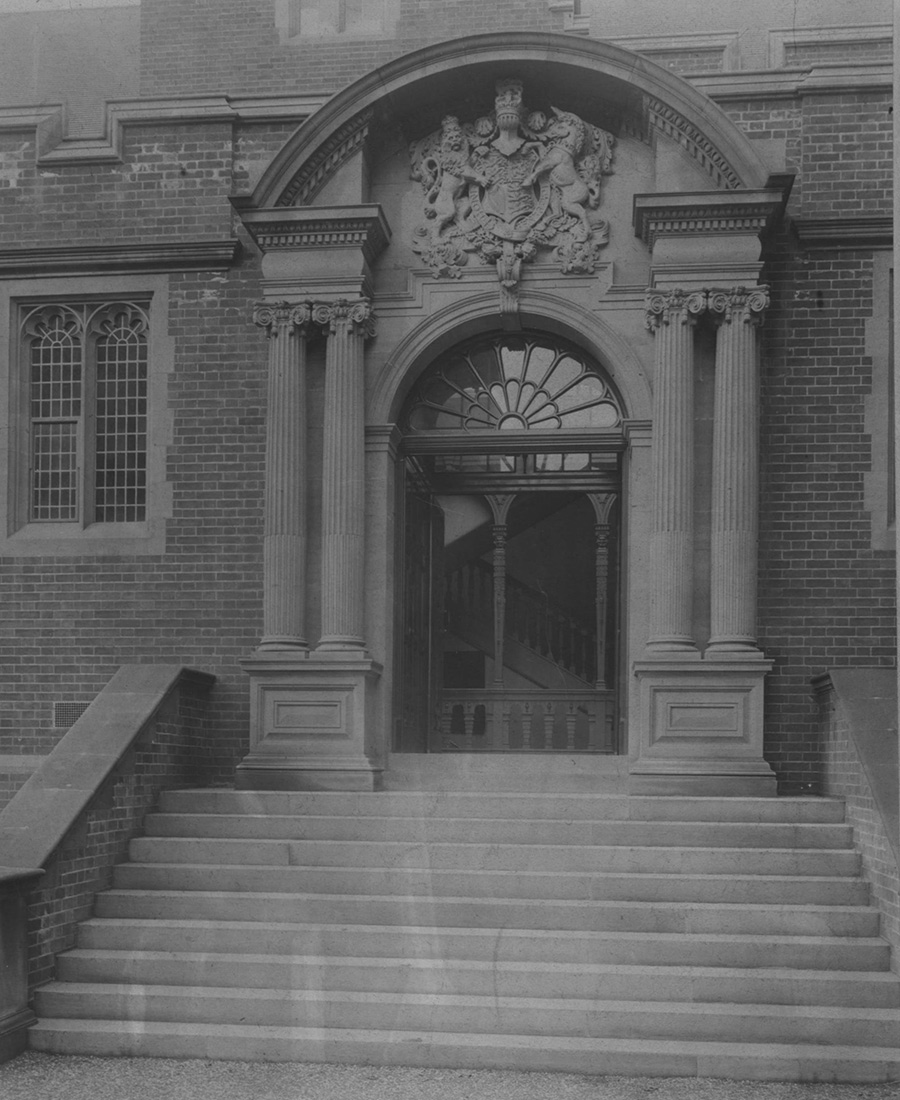

In 1910 the Arts Committee which managed the Department aimed to ‘to draft an appeal for subscriptions towards the erection and maintenance of new buildings for the school.’ The Foundation stone for the building which now houses the Hatton Gallery and the Fine Art Department was laid by John Bell Simpson on April 25 1911.

Designed by W.H. Knowles, the building was opened in 1912 and was known as the King Edward VII School of Art. Hatton was made the first Head of School, before serving as the inaugural Professor of Fine Art from 1917 until his death in 1926.

With the outbreak of war in August 1914, many University buildings were taken over for hospital use, including the art gallery within the King Edward VII School of Art until October 1919.

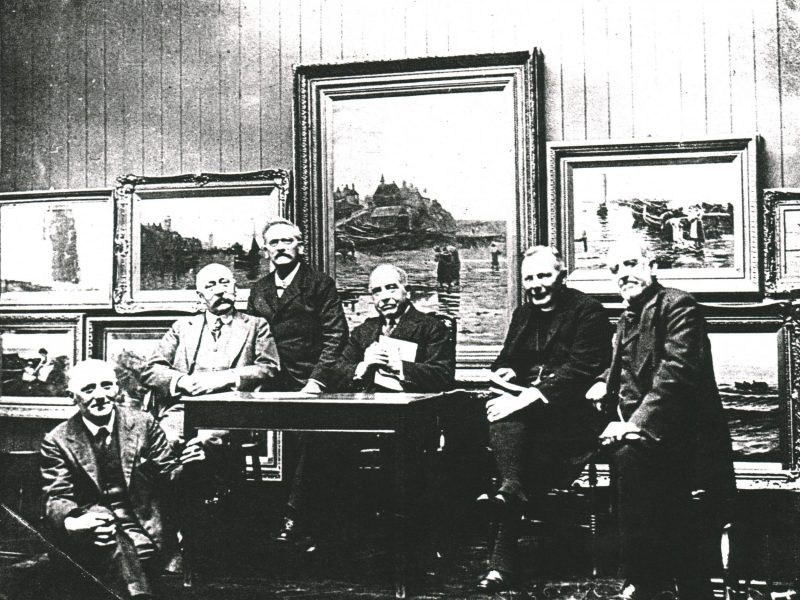

Following the war Professor Hatton organised occasional exhibitions in the gallery, which was considered central to the School of Art and contributed towards the teaching activities of the department showing both historical works, as well as examples of developments in contemporary art and design, such as the exhibition of work by local painter Robert Jobling in 1923.

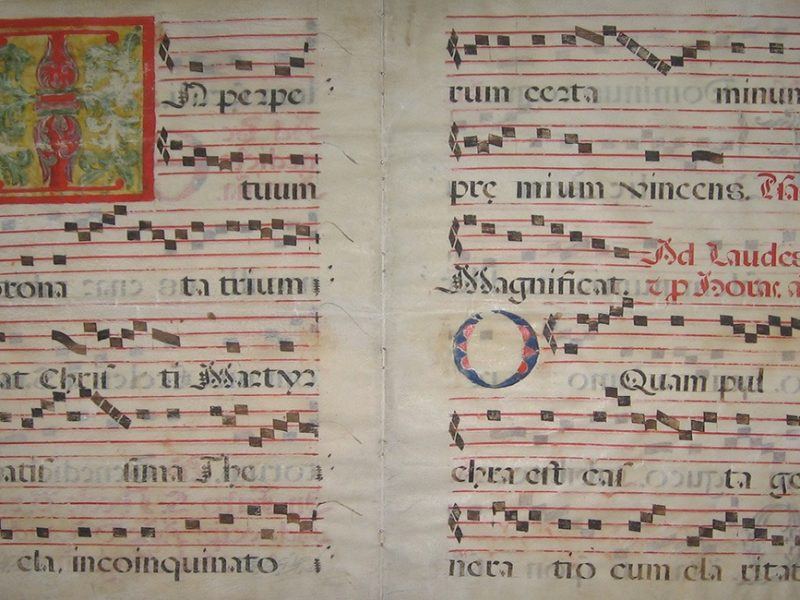

The earliest items in the Hatton’s Collection came as donations from Professor Hatton himself, who in 1919 gave his small collection of Indian miniatures, copy of Burgkmair’s Triumphal Procession dating from the early 16th century and a number of fragments from illuminated manuscripts.

1919 also saw two significant donations of works by unrelated Charlton families. George Charlton donated over 1,000 works by his brother William Henry Charlton (1846-1918). Born in Newcastle, he travelled across Britain and Europe, studying for a time at Académie Julian in Paris. The donation included examples of his drawings, watercolours, lithographs, sketchbooks, oils and etchings, principally of landscapes. The gift also included some etchings and sketches by Joseph Crawhall jnr.

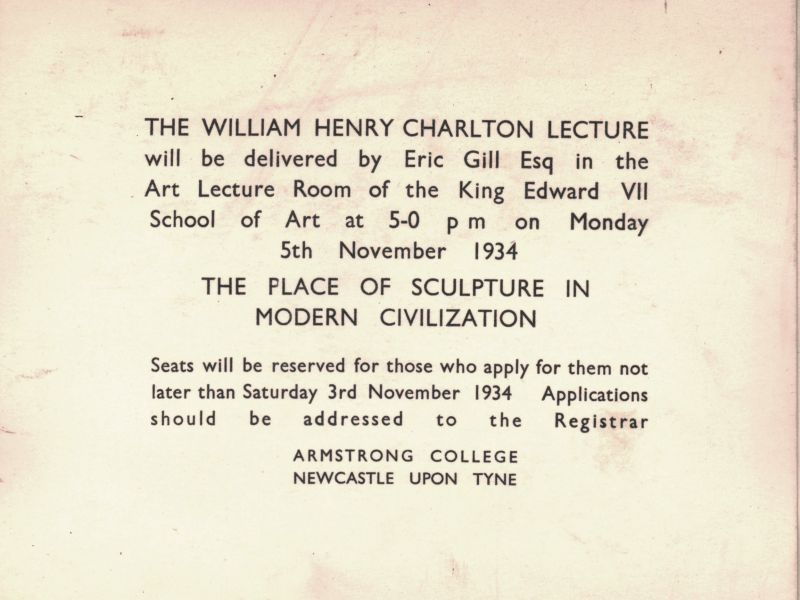

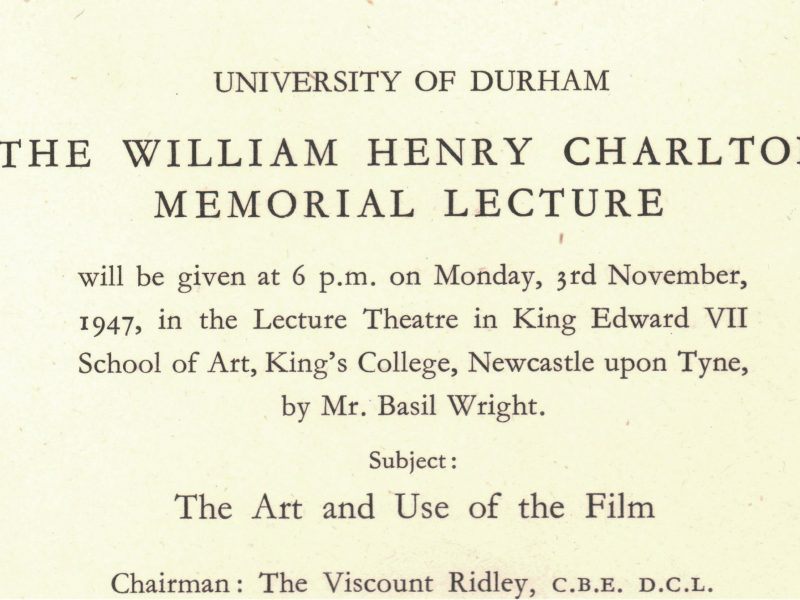

Another significant part of George Charlton’s gift was the provision of an initial £800 to inaugurate an annual ‘Charlton Lecture’, which would continue to the present day, usually given by an eminent art historian, or more occasionally an artist. Up until the 1970s the lecture would also be published in booklet form.

Around 100 works by John Charlton (1849-1917) and his son Hugh (died 1916) were also donated in 1919. It was recorded that sketch books and loose studies belonging to both John and Hugh were presented to the Department by members of their family. The two Charlton families are not thought to be related but it is likely that William and John knew each other and both served as members of the Armstrong College Arts Committee between 1912 and 1917.

The art school developed and expanded during the 1920s and 30s, first under E.M.O’R. Dickey (Professor, 1926-31) who had studied painting under Harold Gilman at the Westminster School of Art and would later become inspector of art for the Ministry of Education (1931-57), and then Allan Douglass Mainds (Professor, 1931-45). Following his death in 1926 the Art Committee decided to name the school’s gallery after Professor Hatton, some exhibitions from this period included ‘Modern etchings from the collection of Mr Alan Kirkwood’ in 1929, an exhibition of weaving and small sculpture (including works by Henry Moore) in 1932 and in the same year a show for ex-student and tutor Byron Dawson.

In 1934 artist Eric Gill delivered the Charlton lecture on the subject of ‘The Place of Sculpture in Ancient Civilization’.

The various Newcastle based colleges, including the art school, governed by Durham University merged to form King's College in 1937 and they would remain under that name until 1963, when the federal University was dissolved and King's became the University of Newcastle upon Tyne (this was changed to Newcastle University in 2006).

During World War 2 Charlton Lectures and exhibitions in the Hatton Gallery continued. In 1939 the then Director of the National Gallery, Sir Kenneth Clark spoke about ‘The Aesthetics of Still Life’. The following year local historian C.H. Hunter Blair’s talk on ‘Mediaeval English Heraldry’ accompanied a related exhibition in the Hatton Gallery.

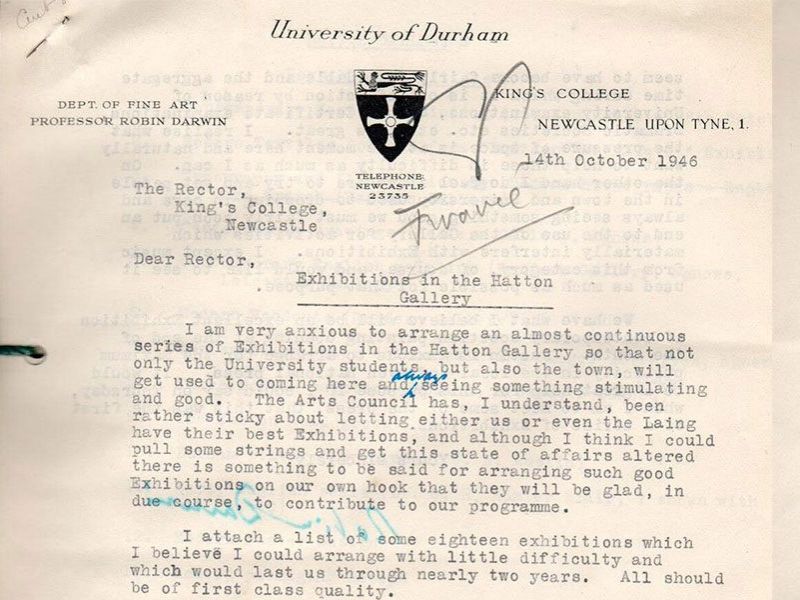

The appointment of Robin Darwin as Professor in 1946 began a process of modernisation and development that Lawrence Gowing would pursue through the 1950s. Darwin had been employed from 1945-46 as education officer in the newly formed Council of Industrial Design, where he reported on the training of industrial designers, and specifically the proper role of the Royal College of Art in London (which in 1948 he would himself become Head of).

One of Darwin’s immediate concerns was to establish ‘an almost continuous series of exhibitions’ for both the students and town, to encourage the Arts Council to lend their best exhibitions and to develop shows ‘on our own hook’. He goes on to outline to the Rector (Lord Eustace Percy) 18 possible shows, suggests a Friends group to help subsidise the programme, emphasises that it was essential for students to see good contemporary art and argues that the Gallery should be used for its proper intended purpose rather than examinations, dramatic societies etc.

The Rector would reply to Darwin that ‘I will also put to the Finance Committee on Nov 4 the idea of opening a Hatton Gallery Exhibition Fund which might attract private subscriptions.’ Darwin’s tenure was very brief so he was unable to see all his ideas come to fruition, but he certainly established the context in which Gowing was able to develop the Hatton as an important centre for both historic and contemporary art exhibitions.

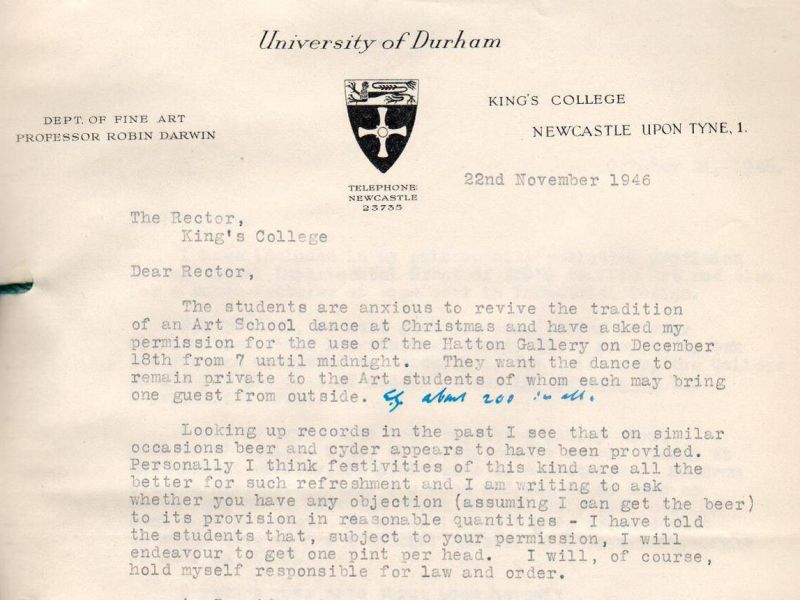

Darwin was very supportive of the students’ needs, in November 1946 he wrote to the Rector regarding the possibility of reviving the students Christmas dance, suggesting drinks might be provided and that social activities should be encouraged. Lord Percy’s wonderful reply permits Darwin to acquire the drinks (recommending Newcastle Breweries’ draught cyder), though he asks that he check the legalities with Steward of the Union and suggests that students will have to bring their own sandwiches.